Guilherme Ferreira, MixITiN’s ESR3, reporting from Helsingør, Denmark about his adventures in Crete

May 2019

When was the last time that you ever felt that you did not know how to read? Probably some years ago… maybe when you were 6 years old? Well, I felt just like that when I reached Crete (Greece), in June of 2018 when I was 23 years old. I had just arrived for my first secondment, as ESR3 of the MSCA ITN MixITiN project.

It is always strange when we travel to a foreign country and do not know the language, but it is even worse to reach a place where you cannot even recognise the alphabet! I felt like I was looking into a set of randomly placed hieroglyphs with no meaning at all. Can you imagine trying to buy an item at the supermarket and the only thing you know is that there is a special code that you have to remember every time you want to buy it again?

After the initial shock of the very different written language, I was introduced to the staff at the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research whose names also looked like hieroglyphs to me. However, when they pronounced their names, the coded language suddenly started to make sense to me! I could finally see the words behind the symbols!

It took me a while to adjust to the situation, but I learned a very valuable lesson from this experience. Something that might look incredibly hard to you may be the most basic knowledge for someone else and vice-versa. This realisation made me think about my research and about how to communicate it to other people who know nothing about it. I have started applying this mental exercise for many of my daily activities as well. It made me think of how often one could try to make a point on a discussion but find difficulties in explaining it properly? Probably a lot more often than one would like to admit… Does this have to do solely with our listener’s interpretation skills or may be it is also affected by our own skill in providing explanations?

Since you are here, you probably already know that a mixotrophic protist mixes two distinct ‘trophys, or ways of obtaining food (if you did not know this, take a look at our homepage, you will like it). A mixotroph can make its own food like a plant (termed autotrophy) and hunt like an animal (also known as heterotrophy), all within a single cell. So what? What does this knowledge add to your life? Perhaps not much and you are about to stop reading this text… Wait a minute, because last year I was just as clueless as you are now! Besides, let us not forget the valuable lesson that I learned in Greece: by the time you finish reading this blog entry you should have learned something new, otherwise I will have failed in my quest to decode a complex message into something that we can all understand.

First of all, I went to Crete with the purpose of learning about the taxonomy of ciliates. Did I just say two words that are meaningless to you? Worry no more because not that long ago these words were meaningless to me as well!

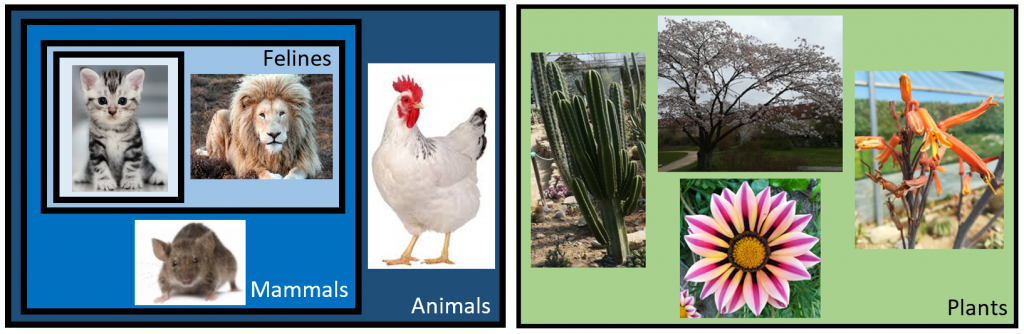

First things first: taxonomy is the classification of individuals based on morphological characteristics or, if you prefer it, the grouping of organisms according to their similarities. For instance, we can see that a cat has some things in common with a lion but not so many with a mouse. Yet, a cat has more similarities to a mouse than to a chicken, as they are both mammals and a chicken is not. Still, they are all animals, which implies that plants should have their own box. Taxonomy is the science that enables us to group cats, lions and mice into mammals, chickens into a group which also includes other animals, and plants into their own group.

What about ciliates? Well, you may have heard about Paramecia? No one wants to get Paramecia because these cause some nasty gut diseases. Paramecia are in fact a group of ciliates called Paramecium. In general, a ciliate is an organism that possesses some hair-like features that allow it to move around, the cilia, hence their name.

The cilia work for the ciliates pretty much like how the tail works for an alligator. An alligator uses its tail to swim through the water and the cilia allow the ciliate to move around, as shown in the video recorded by ESR7 Maira Maselli.

The one and only difference between an alligator and a ciliate would be that the alligator would need to possess many tails in order to resemble a ciliate. And, be a single cell roughly the size of the diameter of your hair (one-twentieth of a millimetre)! It would also need to eat almost 2.5 times its own body weight in a single day, every day. Hum, you get the point…

So, going back to my original question, why was it important for me to know how to group ciliates correctly? Can one simply not ignore their presence and move on with life? The answer is YES but the REAL QUESTION is should you ignore their presence? By all means, NO!!! There are many types of ciliates, and like all things on this planet, some are good for us whereas others cause us some serious issues, like the Paramecium that I was talking about. [By the way, be careful about describing something as “good” or “bad”. I certainly do not think that a cat thinks himself as bad when it kills a mouse whereas from the mouse’s perspective, a cat is the purest incarnation of evil.]

Most of the ciliates that live in our oceans are typically “good”, because they are nutritionally good food for the larger plankton, which in turn are eaten by the fish that we like to eat. At least I do, especially while enjoying a sunset by the beach with a mojito in my hand. So, simply put, without ciliates in our oceans, there may not be any fish left for us to eat alongside a mojito.

If you are still reading this blog and are wondering what does this have to do with mixotrophs, then it may be time to tell you that many (but not all!) ciliate species in our oceans are mixotrophs, which is the same as saying that they are voracious predators and yet are able to produce their own food using chloroplasts from others. Though morally ambiguous, the act of stealing someone else’s food factories is a rather ingenious trick that allows ciliates to thrive on virtually every environment on the planet. An interesting feature of these food factories is that they become fluorescent when irradiated with UV light, which is a rather simple way of assessing if a ciliate is a pure predator (a heterotroph) or a mixotroph.

A) The heterotroph Strombidium sp. B) The mixotroph Strombidum conicum C) The mixotroph Mesodinium rubrum

Thus, it is now easy to understand the need for the knowledge of how to properly put ciliates in the correct taxonomic box. Their presence/absence affects the flow of energy and matter throughout the food web.

Mixotrophic and heterotrophic ciliates exhibit profound physiological differences, and these differences are the key to understanding their role in our oceans. Can you imagine a world without fish and mojito on the beach? I cannot, and that is why we are attempting to know which cilaites are out there and what are they doing!

And now, since I already know who they are, it is time to redirect my attention to what are they doing, and that is exactly why I am now in Denmark, where I will be until the end of June 2019. I will get back to you again, once I have unveiled more mysteries that still surround mixotrophic ciliates! See you soon!