Notes from ESR 6, Andreas Norlin.

October 2019

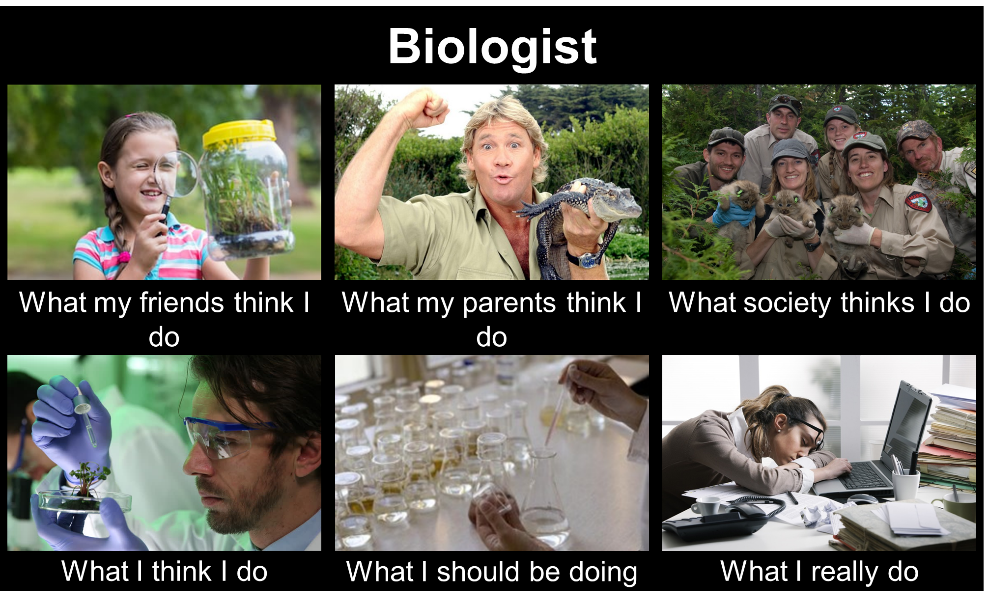

Being a biologist can mean many things. For me, when I started studying biology, it meant that I would be able to study the natural world and hopefully go out into the field and experience it myself. This was of course only part of the truth about being a biologist, as modern biologists spend a lot of time either in the lab or in front of a computer.

In Denmark, we have a way of dividing biologist into two major groups: Biologists are either considered as a “gummistøvle-biolog”, which literally translates into “wellies biologist”, or as a “kittel-biolog”, meaning “lab-coat biologist”. A wellies biologist works in an area of study where the focus is on fieldwork with less time- or even no time spent in the lab. A lab coat biologist can then be seen as the opposite; spending no time in the field and almost all the work in a lab wearing a lab coat. This is definitely a simplification of the truth, but it makes sense to some extent and one thing almost all biologists love is to put things into boxes with definitions.

I graduated with a MSc in marine biology, for which I did some fieldwork over the years – which I quite enjoyed. The work I did for my master thesis was done purely in the lab and culture rooms – which I also found enjoyable. Working with protists is not easy for various reasons and it was exciting to see my cultures grow, and conduct experiments on them.

At the end, even though I had spent most of my time in the lab I still considered myself as a “wellies biologist” since my work still had potential for a career including fieldwork.

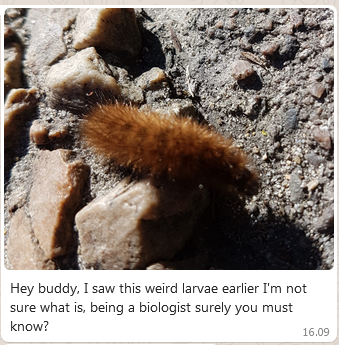

I assume most biologists will agree with me, that the rest of the world most likely associates them with my previous description of a “wellies biologist”. Wrongly so, as there are probably many more trained biologists in labs who never go out to do fieldwork than trained biologists who actually do. So, what happens if you are a trained biologist, who is neither a “wellies biologist” nor a “lab-coat biologist”? Computers in biology, and in all other sciences for that matter, have become increasingly more important to the point where I would argue that no one can do modern science without the aid of a computer. So there is a third group of biologists; computer biologists, who will not spend the majority of their work pipetting, spreading cells on agar or count cell samples, nor will they go into the field tagging animals, set up beetle traps, take water samples or note down behavioural patterns. The computer biologist will sit in front of their computer working with big datasets, creating mathematical or statistical models or run simulations.

When I started as a biology student, I would never have imagined a future where I would not frequently go out into nature to study the natural world. However, back then I did not know the power of modelling. My graphs were made using specialized software and mathematics or statistics were done crudely using various spreadsheets; all the programs I used had a relatively user-friendly graphical user interface (GUI). Programs with GUIs make it easier for the user to complete tasks but then they are limited by what the program allows them to do. Programming languages on the other hand, do not limit the user by anything else than their own knowledge and experience but come with a much steeper learning curve. So, as time has passed and my perspectives have changed, I have come to appreciate the beauty, and freedom of programming, which has now led me to my current position as ESR 6 in MixITiN. Now I am a computer biologist. I sit in front of my computer developing system dynamics models, which I use to run simulations of the natural world; exploring gaps in our knowledge of eSNCM (endosymbiotic Specialist Non-Constitutive Mixoplankton).

This is very different from what I ever imagined being a biologist could be, but I am very excited about it. I get to play a virtual god; creating virtual life, writing virtual laws that cannot be broken and killing my virtual mixoplankton off as I see fit. Of course, the goal is to create a representation of the real world, using mathematical equations and calculus to explore very complex interactions. This is not just done to satisfy the curiosity of a scientist isolated from nature, but to guide future experiments that will attempt to confirm or reject the hypotheses sprouting from running simulations. In large terms, the aim of a computer biologist is to work together with the experimental biologist creating a symbiotic relationship where ideas, concepts and data are exchanged equally between the two groups.

Am I still a real biologist or have I become something else? Can you consider yourself a biologist if your work does not directly involve living organisms? To both of these questions my obvious answer is: Yes! I still consider myself a biologist; science evolves and computer modelling is yet another tool in the toolbox of the modern biologist.